The previous post about architecture received some great questions, so I decided to analyze them in more detail in a separate publication. The previous post about architecture received some great questions, so I decided to analyze them in more detail in a separate publication.

Quick recap

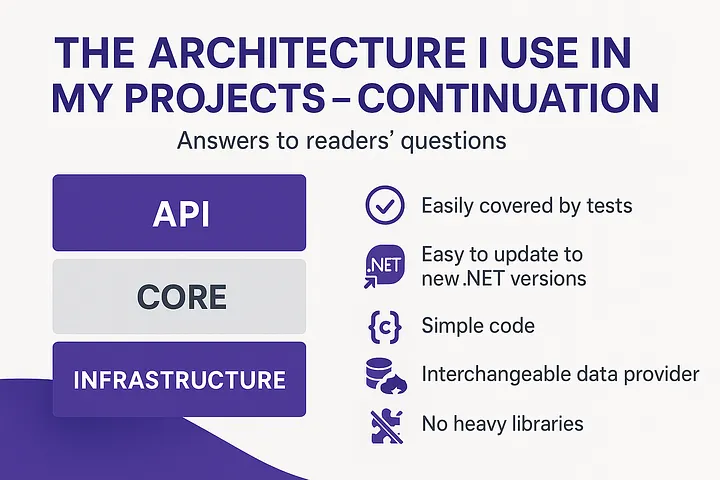

Let’s recall the main requirements:

- The application should be easy to cover with tests.

- The application should be easy to update.

- The code should be simple.

- The data provider should be easy to replace.

- Avoid using libraries that influence the overall architecture.

These requirements are focused on practical application. The goal is not to strictly adhere to DDD, CQRS, Event Sourcing, etc.

Why I avoid external libraries that deeply penetrate the architecture

Using external libraries always carries risks. Paid libraries can significantly increase support costs. The author of an open-source library might lose motivation to maintain it, introduce malicious code, or change the license. You can fork a library, but that transfers the maintenance burden to you.

If a library is used only in a limited part of the application, it is usually acceptable. The problem arises when a library is tightly integrated into the overall architecture.

Such libraries are often adopted to reduce boilerplate (for example, by using reflection). But reduced lines of code is not the same as better design. Modern IDEs already provide excellent completion and navigation. By avoiding deep framework libraries we get strong benefits: project independence, easier debugging, and simpler code navigation.

Why I prefer use-case classes instead of large services

A common question is why create a separate use-case class for each action instead of a single service with multiple methods. Although a large service might initially seem convenient, over time it often grows into a massive class (1000+ lines) with dozens of methods and dependencies. That makes testing and reasoning about behavior much harder.

Keeping one use case per action encourages single-responsibility, smaller dependency graphs, and simpler tests.

Can we use base classes for use cases or repositories?

I prefer not to. Inheriting from base classes can make it harder to extract functionality into a separate service or microservice. It tends to enforce specific behaviors and increases coupling.

When possible, favour small, explicit interfaces and composition over inheritance.

EF and the repository pattern

Some teams assume that using EF (Entity Framework) removes the need for an additional abstraction because it already hides the database. In practice, that creates a strong dependency on the ORM.

In my architecture, all interaction with EF is contained within the Infrastructure layer, inside each repository implementation. I avoid a shared base repository — each repository is explicit and independent.